Ze’ev Raban (1890-1970) was a leading painter, decorative artist, and industrial designer of the Bezalel school style, and was one of the founders of the Israeli art world.

Wolf Rawicki (later Ze'ev Raban) was born in Łódź, Congress Poland, and began his studies there. He continued his studies in sculpture and architectural ornamentationat a number of European art academies. These included the School of Applied Art in Munich at the height of the Jugendstil movement, the neo-classical studio of Marius-Jean-Antonin Mercié at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, then a center of Art Nouveau, under symbolist and idealistartists Victor Rosseau and Constant Montald.

Under the influence of Boris Schatz, the founder of the Bezalel Academy, Raban moved to the land of Israel in 1912 during the wave of immigration known as the Second Aliyah. He joined the faculty of the Bezalel school, and soon took on a central role there as a teacher of repoussé, painting, and sculpture. He also directed the academy's Graphics Press and the Industrial Art Studio. By 1914, most of the works produced in the school's workshops were of his design. He continued teaching until 1929.[2]

In 1921, he participated in the historic art exhibition at the Tower of David, the first exhibit of Hebrew artists in Palestine, which became the first of a yearly series of such exhibits.

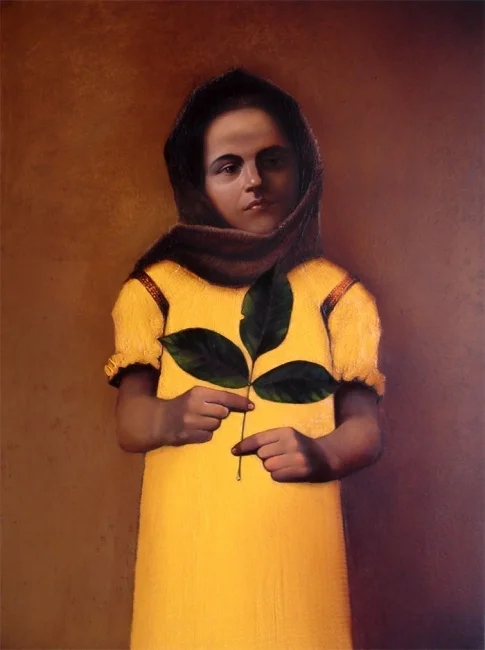

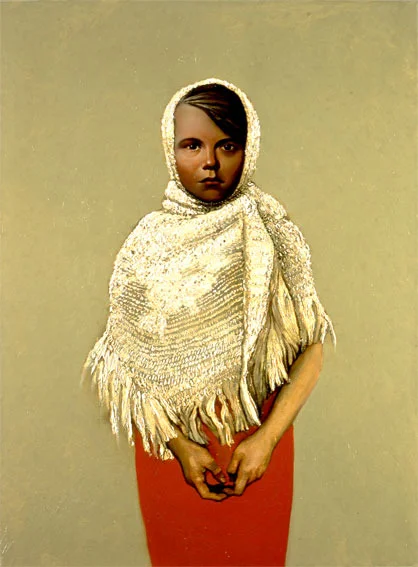

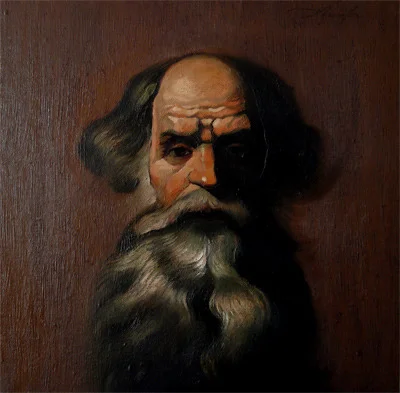

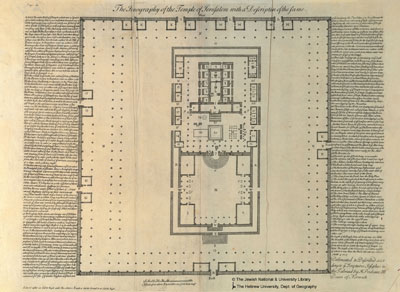

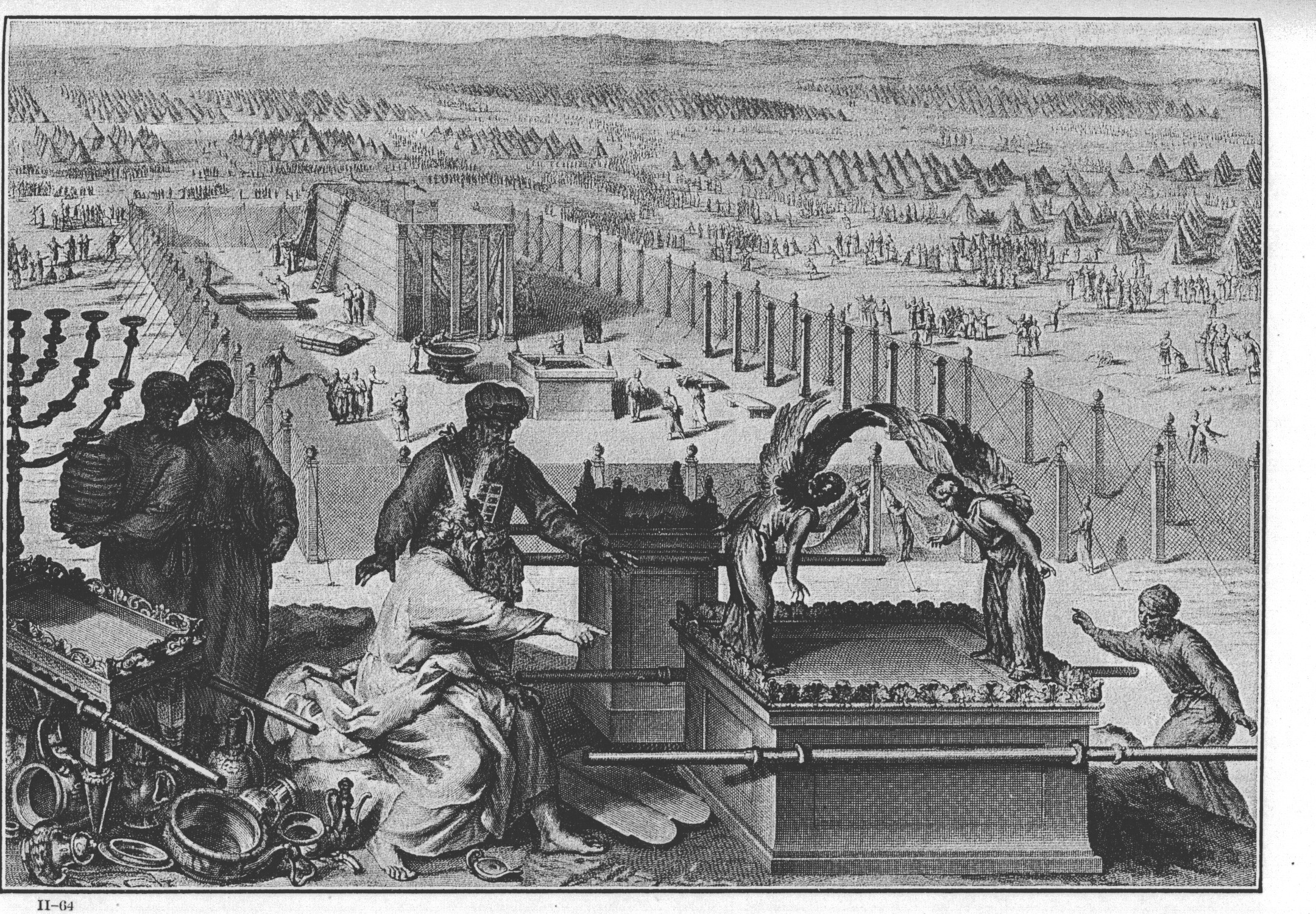

Raban is regarded as a leading member of the Bezalel school art style, in which artists portrayed both Biblical and Zionist themes in a style influenced by the European jugendstil (similar to Art Nouveau) and by traditional Persian and Syrian styles. Exemplars of this style are Rabban's illustrated editions of the Book of Ruth, Song of Songs, Book of Job, Book of Esther, and the Passover Hagadah.[2]

Like other European art nouveau artists of the period such as Alphonse Mucha Raban combined commercial commissions with uncommissioned paintings. Raban designed the decorative elements of such important Jerusalem buildings as the King David Hotel and the Jerusalem YMCA,.[3] He also designed a wide range of day-to-day objects, including playing cards (in the suit of leaves, the King is Ahasuerus, the Queen is Esther, and the Jack is Haman), commercial packaging for products such as Hanukkah candles and Jaffa oranges, bank notes, tourism posters, jewelry, and insignia for Zionist institutions.

"Raban easily navigated a wealth of artistic sources and mediums, borrowing and combining ideas from East and West, fine arts and crafts from past and present. His works blended European neoclassicism, Symbolist art and Art Nouveau with oriental forms and techniques to form a distinctive visual lexicon. Versatile and productive, he lent this unique style to most artistic mediums, including the fine arts, illustration, sculpture, repousee, jewellery design, and ceramics."[4]

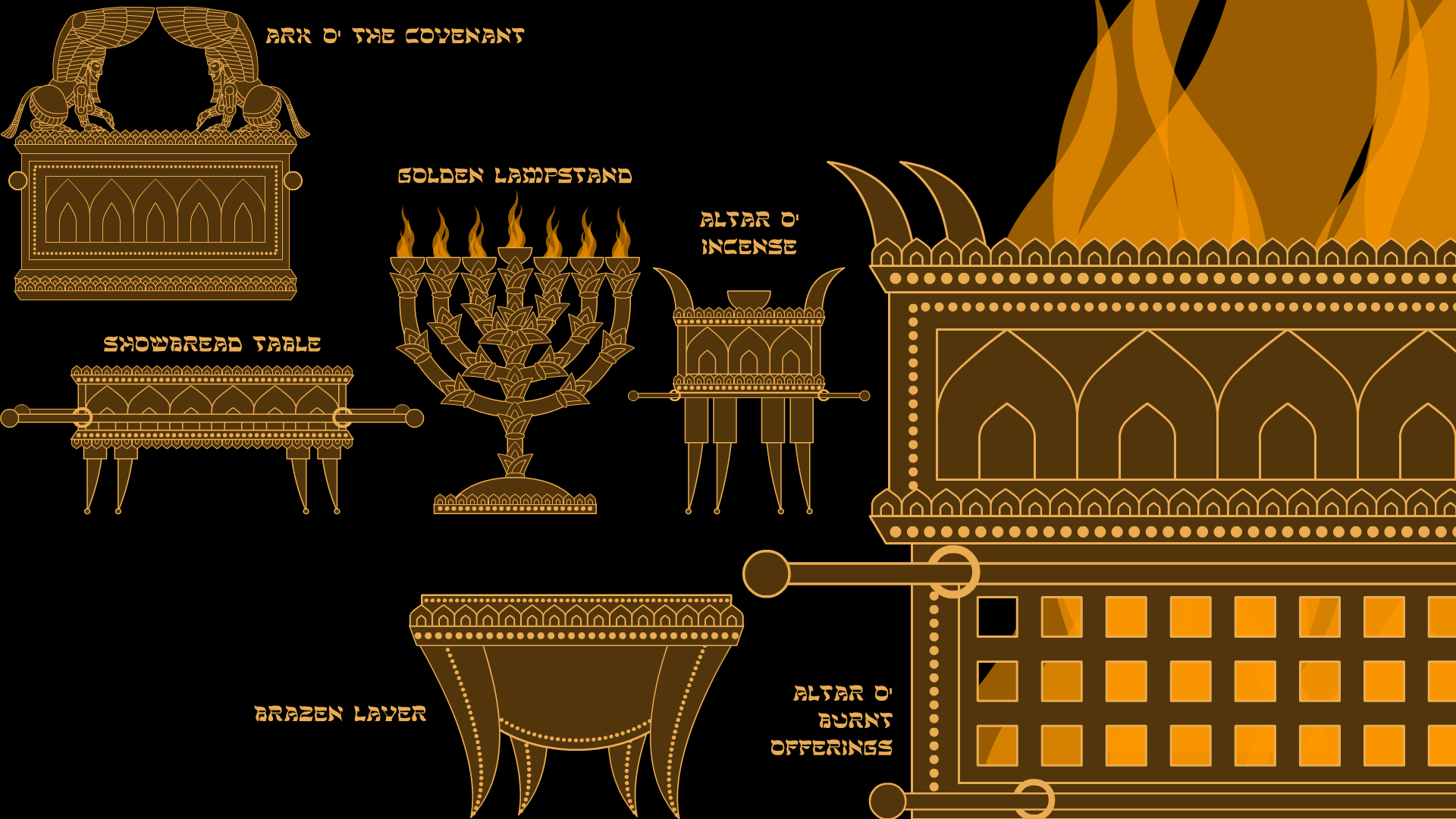

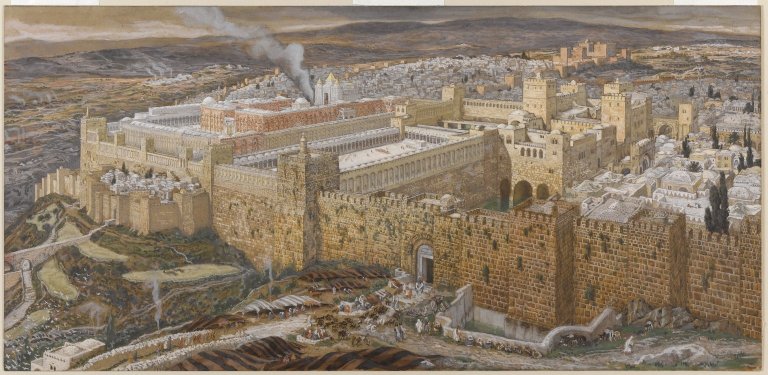

Raban also designed a wide range of Jewish objects, including Hanukkah menorahs, temple windows, and Torah arks.[5] Temple Emanuel (Beaumont, Texas) has a notable set of six windows, each 16-feet high]. The windows were commissioned from Raban in 1922 by Rabbi Samuel Rosinger. Each window depicts an event in the life of one of the principal Hebrew prophets, Jeremiah, Elijah, Elisha, Ezekiel, Moses, and Isaiah.[6]

Raban collaborated with other artists to produce versions of his work as ceramic tiles, a number of which can still be sees on buildings in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, including the Bialik House. The 1925 Lederberg house, at the intersection of Rothschild Boulevard and Allenby Street features a series of large ceramic murals designed by Raban. The four murals show a Jewish pioneer sowing and harvesting, a shepherd, and Jerusalem with a verse from Jeremiah 31:4, "Again I will rebuild thee and thous shalt be rebuilt."[7]

In 2015 one of his works received international attention. The President of Israel, Reuven Rivlin visited at the White House with U.S. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama for the December 2015 Hannukah celebration.[8] Israel's First Lady Nechama Rivlin joined her husband in lighting a menorah made in Israel by Raban, and loaned by the North Carolina Museum of Art’s Judaic Art Gallery. The White House noted: "The design elements of this menorah underscore a theme of coexistence, and its presence in the collection of the Judaic Art Gallery in North Carolina highlights the ties between American Jews and Israeli Jews and the vibrancy of Jewish life in the American South."[9]