In Exodus 31:1-6 and chapters 36 to 39, Bezalel (Hebrew: בְּצַלְאֵל, also transcribed as Betzalel and most accurately as Bəṣalʼēl), was the chief artisan of the Tabernacle[1] and was in charge of building the Ark of the Covenant, assisted by Aholiab. The section in chapter 31 describes his selection as chief artisan, in the context of Moses' vision of how God wanted the tabernacle to be constructed, and chapters 36 to 39 recount the construction process undertaken by Bezalel, Aholiab and every gifted artisan and willing worker, in accordance with the vision.

Elsewhere in the Bible the name occurs only in the genealogical lists of the Book of Chronicles, but according to cuneiform inscriptions a variant form of the same, "Ẓil-Bêl," was borne by a king of Gaza who was a contemporary of Hezekiah and Manasseh.

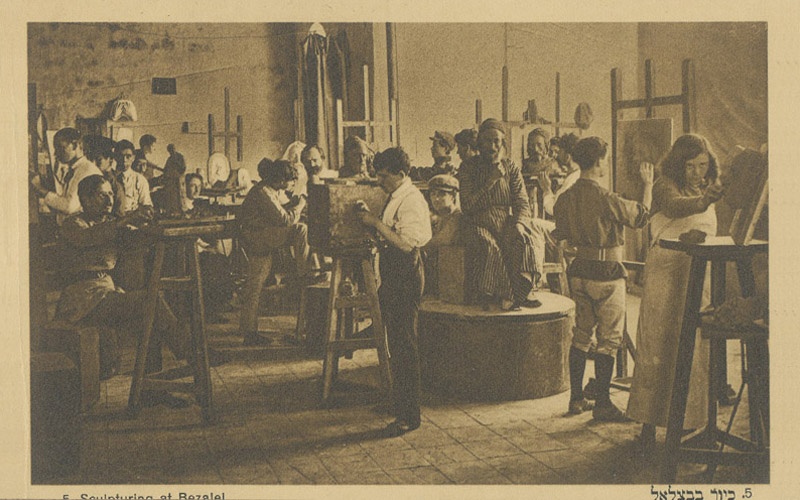

The name "Bezalel" means "in the shadow [protection] of God." Bezalel is described in the genealogical lists as the son of Uri (Exodus 31:1), the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah (I Chronicles 2:18, 19, 20, 50). He was said to be highly gifted as a workman, showing great skill and originality in engraving precious metals and stones and in wood-carving. He was also a master-workman, having many apprentices under him whom he instructed in the arts (Exodus 35:30-35). According to the narrative in Exodus, he was called and endowed by God to direct the construction of the tent of meeting and its sacred furniture, and also to prepare the priests' garments and the oil and incense required for the service.

He was also in charge of the holy oils, incense and priestly vestments.[2] Caleb was his great-grandfather.

The rabbinical tradition relates that when God determined to appoint Bezalel architect of the desert Tabernacle, He asked Moses whether the choice were agreeable to him, and received the reply: "Lord, if he is acceptable to Thee, surely he must be so to me!" At God's command, however, the choice was referred to the people for approval and was endorsed by them. Moses thereupon commanded Bezalel to set about making the Tabernacle, the holy Ark, and the sacred utensils. It is to be noted, however, that Moses mentioned these in somewhat inverted order, putting the Tabernacle last (compare Exodus 25:10, 26:1 et seq., with Exodus 31:1-10). Bezalel sagely suggested to him that men usually build the house first and afterward provide the furnishings; but that, inasmuch as Moses had ordered the Tabernacle to be built last, there was probably some mistake and God's command must have run differently. Compare also Philo, "Leg. Alleg."

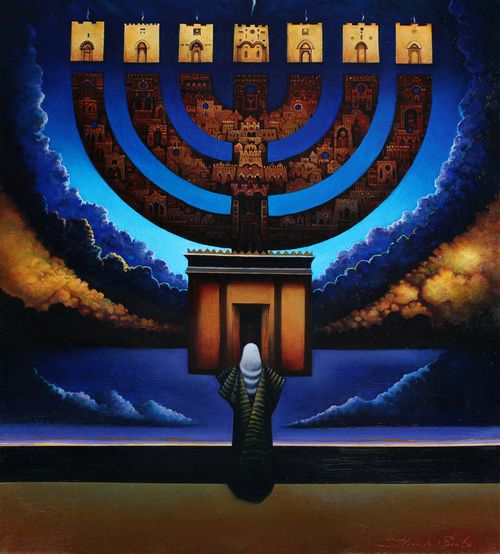

Bezalel possessed such great wisdom that he could combine those letters of the alphabet with which heaven and earth were created; this being the meaning of the statement (Exodus 31:3): "I have filled him . . . with wisdom and knowledge," which were the implements by means of which God created the world, as stated in Proverbs 3:19, 20 (Berakhot 55a). By virtue of his profound wisdom, Bezalel succeeded in erecting a sanctuary which seemed a fit abiding-place for God, who is so exalted in time and space (Exodus R. 34:1; Numbers R. 12:3; Midrash Teh. 91). The candlestick of the sanctuary was of so complicated a nature that Moses could not comprehend it, although God twice showed him a heavenly model; but when he described it to Bezalel, the latter understood immediately, and made it at once; whereupon Moses expressed his admiration for the quick wisdom of Bezalel, saying again that he must have been "in the shadow of God" (Hebrew, "beẓel El") when the heavenly models were shown him (Numbers R. 15:10; compare Exodus R. 1. 2; Berakhot l.c.). Bezalel is said to have been only thirteen years of age when he accomplished his great work (Sanhedrin 69b); he owed his wisdom to the merits of pious parents; his grandfather being Hur and his grandmother Miriam, he was thus a grandnephew of Moses (Exodus R. 48:3, 4).